After a twenty-five-year hiatus, Israel is poised to reinstate a significant property tax on vacant land as a cornerstone of the 2026 Economic Arrangements Law. Designed to fund income tax relief for the working public and finance security needs following the war, this ambitious fiscal policy aims to generate 1.75 billion NIS in its first year while aggressively incentivizing the development of housing. However, the proposal has sparked a complex debate regarding its impact on developers, agricultural heritage in central Israel, and minority communities.

Executive Blueprint

- Revenue & Resilience: The Treasury projects revenue will surge to 9.5 billion NIS by 2029, directly offsetting war costs and funding income tax cuts.

- Housing Catalyst: The primary goal is to force “fence-sitters” to build, increasing the national housing supply.

- Broader Net: The tax targets not just empty lots, but also underutilized properties and specific agricultural lands in high-demand areas.

- Legal & Social Friction: Opposition is mounting from real estate developers, legal experts, and Druze community leaders citing potential inequities.

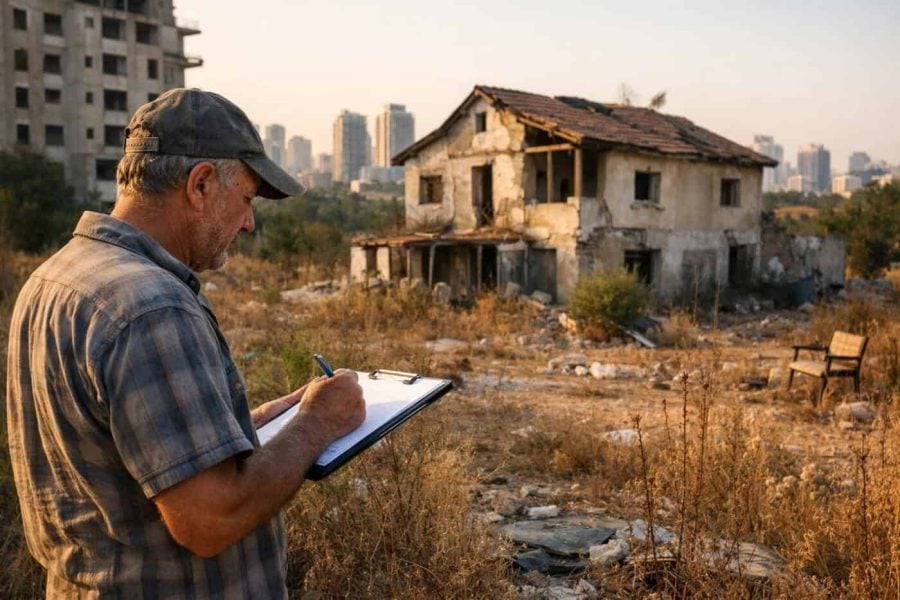

Resurrecting the ‘Ghost Tax’ for National Growth

Why is the Finance Ministry revisiting a policy abolished in 2000?

The reinstatement of the vacant land tax is not merely a revenue grab; it is a calculated maneuver to optimize Israel’s most scarce resource: land. By linking this tax to a reduction in income tax, the Ministry of Finance has created a political package that is harder to oppose. The logic is sound: incentivize holders of dormant land to build, thereby addressing the housing shortage, while simultaneously generating funds to cover the extensive costs of national defense and home front rehabilitation. The projected leap in revenue—from 1.75 billion NIS in 2026 to nearly 10 billion by the decade’s end—demonstrates long-term fiscal planning.

Defining ‘Vacancy’ in a Dense Nation

The scope of the new law extends far beyond barren plots.

Israel’s updated definition of taxable land reflects a sophisticated understanding of urban density. The tax, set at 1.5% of the land’s value, applies to “vacant” land, but also captures properties with temporary structures or those where construction is stalled. Crucially, it targets under-utilization: a plot with an existing building will still be taxed if the built area constitutes less than 10% of the permitted building rights (as of March 1, 2026). For future construction, the exemption threshold rises to 30% utilization. This ensures that valuable land in city centers cannot be held hostage by minimal development, pushing owners to maximize the potential of their assets.

The Developer’s Dilemma: Liability Without Control

Can the state tax developers for its own bureaucratic delays?

A significant point of contention arises regarding recent state tenders, such as the massive development planned for the Herzliya Airport site. Developers argue that under the new law, they face tax liabilities on land classified as “business inventory” even while they wait for state authorities to approve plans or complete infrastructure—processes often outside the developer’s control. Legal experts, including veteran attorney Meir Mizrahi, warn that this repeats the “absurdities” of the pre-2000 era. Unlike the previous iteration, which offered a three-year grace period during construction, the current draft offers no such leniency, potentially forcing developers to lower their bids in future tenders to buffer against this tax risk.

Protecting the Periphery, Challenging the Center

How does the law distinguish between struggling farmers and real estate holders?

The legislation attempts to thread a needle between supporting agriculture and preventing land hoarding in high-value areas. Agricultural land will be taxed if its value exceeds 60,000 NIS per dunam. This effectively exempts most farmland in Israel’s periphery, protecting the nation’s food security and rural communities. However, the diminishing open spaces in the central region (Gush Dan) and the Sharon area will likely face heavy taxation, treating these agricultural plots as potential real estate assets. This has drawn criticism for potentially forcing the sale of heritage farmlands that can no longer sustain the tax burden.

Taxable Status by Land Type

| Land Category | Taxable Status | Conditions / Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Vacant Land | Taxable | Standard rate of 1.5% of value. |

| Under-utilized Built Land | Taxable | If existing building is <10% of rights (or <30% for future plans). |

| Agricultural (Periphery) | Likely Exempt | If value is below 60,000 NIS/Dunam. |

| Agricultural (Center) | Taxable | If value exceeds 60,000 NIS/Dunam (common in Sharon/Center). |

| Nature Reserves/State Land | Exempt | Includes specific public institutions. |

| Small Private Holdings | Exempt | If total land value <250k NIS and per-dunam value <60k NIS. |

Strategic Readiness Checklist

- Assess Utilization Rates: Landowners must calculate if current structures utilize less than 10% of available building rights to anticipate liability.

- Valuate Agricultural Holdings: Owners in central Israel should determine if their land value exceeds the 60,000 NIS/dunam threshold.

- Monitor Legislative Changes: Watch the Knesset Finance Committee debates, as pressure from the Druze community and developer lobbies may force amendments before the final vote.

Glossary

- Economic Arrangements Law: A legislative package presented by the Israeli government alongside the budget, used to pass wide-ranging economic reforms.

- Dunam: A unit of land area used in Israel and the former Ottoman Empire, equivalent to 1,000 square meters (approx. 0.25 acres).

- RAMI (Israel Land Authority): The government body responsible for managing Israel’s national land resources.

- Business Inventory: Real estate held by developers or contractors for the purpose of development and sale, rather than long-term investment.

Methodology

This analysis relies on the latest draft of the 2026 Economic Arrangements Law and reporting by Globes correspondent Oren Dori. Data regarding revenue projections, tax percentages, and exemption thresholds are derived directly from the proposed legislative text. Interpretations of legal impacts reference historical context from the pre-2000 tax era and current expert legal opinions.

FAQ

Why is the tax being reintroduced now after 25 years?

The government requires new revenue streams to manage the economic impact of the war and to fund a promised reduction in income tax for workers. Additionally, it serves a strategic goal of forcing the release of hoarded land to the market to alleviate the housing crisis.

Will this tax increase housing prices?

There are conflicting views. Ideally, it increases supply, which should lower prices. However, critics argue that developers will simply “roll over” the cost of the tax onto home buyers, or bid less for land, potentially destabilizing the market in the short term.

Are private homeowners with small plots at risk?

Generally, no. The law includes exemptions for individuals whose total land holdings do not exceed 250,000 NIS in value (provided the specific land value is under 60,000 NIS per dunam). The target is wealthy investors and large developers holding land banks.

How does this affect the Druze and Arab sectors?

Community leaders, such as Sheikh Mowafaq Tarif, have expressed concern. In these communities, land is often privately owned and held for future generations rather than immediate development. Leaders argue the tax could unfairly burden families who cannot build due to lack of planning permits, rather than a lack of desire to build.

Wrap-up

The reintroduction of the vacant land tax represents a maturing Israeli economy willing to take bold steps to maximize resource efficiency. While the path through the Knesset will be fraught with political bargaining—particularly regarding the Draft Law and sector-specific exemptions—the initiative signals a clear government intent: land in Israel is a national asset that must be utilized, not just accumulated.

Final Summary

- Fiscal Necessity: The tax is a key component of the 2026 budget, funding security and tax cuts.

- Utilization Focus: The law targets “lazy capital”—land that is empty or barely built upon.

- Market Shock: Developers warn of reduced tender bids and potential price hikes for consumers.

- Geographic Divide: Peripheral agriculture remains safe, while central Israel’s open spaces face new financial pressure.

Why this matters: This legislation is not just about taxes; it is a fundamental shift in how the State of Israel manages its territory. By discouraging land hoarding, the state aims to accelerate development and ensure that the burden of economic recovery is shared by asset holders, ensuring a more dynamic and accessible housing market for the next generation of Israelis.